Hello friends,

Since our last correspondence, the U.S. stock market has once again shown its resilience and rewarded the “buy-the-dips” crowd, making a sharp recovery from a 10-15% correction in April. This brief downturn was not unusual and after all, the S&P 500 had been up more than 20% in each of the prior two calendar years. The popular narrative today is that stock prices are high, and some warn of a potential “AI bubble”. As evidence, investors cite today’s relatively high PE ratio (a measure of stock prices relative to earnings) of the broad market in comparison to the very long-term average (i.e. 60-100 years). But the observation that prices look high should not be seen as a signal to act – prices have looked “high” much of the time in our 30+ years in the investment business.

It is best to take market calls with a pinch of salt. It is said, humorously, that economists have predicted nine of the past three recessions. Similarly, our observation is that investors, lay and professional alike, have made far more market calls that failed to come to fruition than those that hit the mark – and if acted upon, these missteps can be very costly in terms of opportunity cost (i.e. the money that you would have made had you sat on your hands). This opportunity cost is rarely accounted for and is not felt by the investor in the same way as the pangs of a loss, but it can nevertheless be very consequential because of its negative effect on compounding. Peter Lynch advises that “far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections, than has been lost in corrections themselves.” Ben Franklin wisely counseled to “Keep your eyes wide open before marriage and half shut afterwards.” This is also a great way to think about your stocks.

To what extent are today’s stock prices “high”? Are valuations worrisome? Are we in an “AI bubble”? Let us look at some of the caveats to these claims.

First, we must acknowledge the stunning financial performance of the magnificent seven – the large tech companies that dominate and skew the S&P 500 in terms of weighting, returns and valuation. Today, they comprise approximately 1/3 of the market value of the S&P 500 index. The magnificent seven are the most profitable companies in the history of the world and they continue to grow at rates far exceeding that of the broad market. According to FactSet, the “Magnificent 7” companies reported actual earnings growth of 26.6% for Q2 2025[1]”. Furthermore, the U.S. continues to incubate companies like the magnificent seven – arguably, increasingly so. U.S. hegemony in technology is a very powerful trend that continues to power the S&P 500 (i.e. Where are the equivalents to Open AI or Nvidia in, say, Europe or Canada?). The U.S. remains a hotbed of innovation, and as such it has been a magnet for investment capital from all over the world. The great Peter Lynch had this to say in an October 6, 2025, interview on CNBC: “It’s a great country. We’re creative. America creates, China duplicates, and Europe legislates[2].” That the S&P 500 has high weightings in highly profitable and fast-growing companies is a complicating factor in comparing today’s PE ratio to the very long-term average of, say 60-100 years. Clearly, the S&P 500 constituents for much of the 20th century did not include anything close to the likes of say, Meta Platforms or Amazon.com. In 2004, 19% of the value of the S&P 500 was technology – today, it is 46%. There can be little debate that the economics of the Magnificent Seven and their ilk are far superior to market heavyweights in, say, the 1970’s or 1980’s.

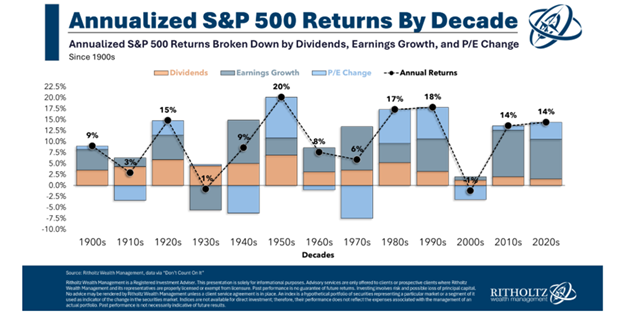

Further, the rate of earnings growth (a big part of the intrinsic value of companies, generally) of U.S. public companies have been well above average over the past 15+ years. Author and portfolio manager Ben Carlson made this observation in a recent memo to clients titled “Why is the Stock Market Up So Much in the 2020s?”.

In Carlson’s view, “If you want to know what’s been driving the U.S. stock market higher, look no further than earnings”. He explains that “in the 2010s we had annual earnings growth of nearly 11%. Earnings have grown at just shy of 10% per year in the 2020s. That’s much higher than the long-term average of around 5% per year[3]” [emphasis added].

As you can see from the graphic below, what is powering the S&P in the 2010s and 2020s is primarily earnings growth and not just rising valuations (i.e. an increase in the PE ratio).

Lastly, some observers claim that we are in an “AI bubble”. It is true that the amount of capital being spent on AI infrastructure is simply stupendous – trillions taken together. Individual companies such as Meta Platforms, Microsoft, Alphabet and Oracle have budgeted hundreds of billions of dollars in capex – largely to build AI infrastructure. Here are a few examples: Meta Platforms is spending US$30 billion on a planned data center complex in Louisiana that it says will eventually be similar in size to Manhattan. Open AI has committed to spending $1.4 trillion on datacenters in the coming years despite that the company projects revenue this year of ~ $20 billion.

Some are concerned that the unprecedented level of spending on AI is analogous to the dot.com / telecom bubble in the late 1990s. At that time, companies such as Global Crossing, Worldcom and Lucent went on a debt-fueled spending spree on fiber networks, leading to a glut and a wave of business failures. It is important to note that investors in that day were not wrong about the commercial prospects of the internet – arguably, the seeds planted during that era led to the extraordinary performance of U.S. indices such as the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq 100 relative to the world over the ensuing 25 years. The bursting of the dot.com bubble was a period of creative destruction that was followed by an era of progress, wealth creation, and outperformance of U.S. stocks. We asked Google’s AI model, Gemini, to compare the U.S. market to that of Europe over the past 20 years (We have new and younger blood here at APEX to teach us such things. Thank you, Connor!). Here are the highlights:

Over the past 20 years, U.S. stocks have returned close to double that of Europe. (S&P 500 average annualized return ~11.1% vs. Europe STOXX 600 average annual return ~6.2%). Gemini also adds the following observations:

Reasons for Outperformance: The US market’s outperformance is often attributed to several factors including:

Sector Composition: The S&P 500 has a higher concentration of fast-growing technology and growth companies compared to the more traditional and financial sector-heavy European indices.

Economic Growth: Stronger relative economic growth in the US has supported higher corporate earnings and market valuations.

Smart fellow that Gemini.

To be sure there are pockets of extreme valuation and potential “irrational exuberance” in AI-related stocks. There certainly will be some measure of Schumpeterian creative destruction similar to the dot.com era in the evolution of AI. There will be winners and losers. Returns will be far from linear but investors in U.S. stocks stand to gain from this profoundly important innovation. Here is what Sam Altman (CEO and founder of Open AI) has to say: “Are we in a phase where investors as a whole are overexcited about AI? In my opinion, yes. Is AI the most important thing to happen in a very long time? My opinion is also yes.[4]”

Our take is this:

- We are in an AI boom, but not necessarily an AI bubble;

- Some measure of creative destruction will follow the formative years of AI; some or perhaps many companies will fail;

- It’s too early to lay bets on AI winners and losers;

- AI has enormous implications for human progress and further gains in living standards;

- Today’s AI big spenders are some of the most profitable companies in the history of the world – this isn’t 1999; and

- Today’s U.S. stock prices may be correctly discounting a very significant bonanza of profits stemming from AI. Markets are very intelligent – theirs is a dispersed knowledge that far outweighs the knowledge of any one individual. Who’s to say they are wrong? Fed Chair Alan Grenspan in 1996 was correct in saying that bubbles are only obvious in hindsight. On Dec. 5, 1996, he made his now infamous speech in which he first uttered the phrase “irrational exuberance”. His specific words were, “How do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions?”

It is worth noting that that valuations on U.S. stocks have remained persistently higher in the 21st century, relative to the prior several decades. This era happens to coincide with the acceleration of U.S. global technology dominance. We see this trend continuing.

We aren’t making the case here that we are in a new era, or “this time is different” – we are well aware of the folly of pollyannish thinking. Rather, we believe that it is not at clear that stocks are nearing bubble territory as some proclaim. We see U.S. stocks as fully valued – “lofty but not nutty”, as Howard Marks has recently opined. Sir John Templeton famously said that the four most dangerous words in investing are “this time is different”, but he later added that in fact, 20% of the time, things really are different. Howard Marks touched on this topic in a recent memo[5]:

“So, on one hand, “it’s different this time” is a recurring bull-market cliche that always bears scrutiny and on the other hand, failing to recognize when things actually are different is something that stands between the average investor and superiority.” [emphasis, ours].

After having made the case that high PE ratios might not be worrisome, we must also acknowledge that high valuations and near-universal bullish sentiment is an unappealing backdrop for making new investments. It is difficult to find bargains in stocks. Stocks that are generally regarded as “quality”, with obvious wide and durable moats now routinely sport valuations of 30-40 x earnings, making the risk / reward payoff much more uncertain. We don’t make predictions about the broad market, but market conditions do influence our appetite for stocks. When most things look expensive, we do less. We maintain awareness of the environment (i.e. the economy, interest rates, stock valuations, etc.) but our eyes remain half shut with respect to these “macro” indicators and the omnipresent slate of worries that can tempt investors to tinker with their long-term investments. Our best guess is that the current environment warrants caution and an emphasis on quality.

Many of you will know that we invest “the Warren Buffett way”. As a refresher, we think of stocks like a piece of a business, we don’t guess about macro events, we don’t “trade” stocks – we buy and hold, we like to buy “quality” (companies with strong competitive advantages and good prospects), and lastly, we try not to overpay. Then we try to be patient.

This has long been our framework for investing. There are other approaches to investing, such as buying momentum (popular stocks), buying so-called “value” stocks, taking a “top-down” approach (using an economic forecast to choose securities and weightings), or actively trading stocks in an effort to buy low and sell high. Alternatively, you may choose to invest in “alternatives”, or “alts” in market parlance. These strategies include private equity / credit, “real” assets such as real estate, etc. – anything that falls outside the traditional categories of stocks, bonds, and cash. Marketing claims include that alts have lower levels of volatility relative to public market securities. But risks abound in this space, in our view. In our experience, most investors in alts do not have a good understanding of what they own, nor do they understand the strategies, the risks or the fine print that spells out very important details such as liquidity. Following is a comment from a Toronto-based portfolio manager that captures the risk inherent in “alts”:

“Please don’t buy any alternative asset without reading the fine print. That 8-10% yield it is dangling, may be partially return of capital, highly levered, may own a bunch of risky assets and may have the right to gate your funds and stop paying any income”.

As one online author put it: investors “have been told bedtime stories about magical “low volatility” private assets”.

One category of alts is known as “private credit” (i.e. debt investments that are not issued by banks and are not issued or traded in an open market). Unlike banks, these lenders are not regulated. Since the Great Financial Crisis of 2009, private credit has grown to represent a very large part of the lending business. According to Barron’s, “private credit has roughly tripled in assets in the past five years, and now consists of more than $1.7 trillion.[6]” More banking regulation has shifted business toward these private, unregulated entities. Strategies employed by private credit funds are often opaque and may employ leverage. A recent Barron’s article had this say: “Private lending has exploded in recent years… trillions of dollars have poured into funds managed by private credit giants like Apollo, Ares, Blackstone, KKR, and enough Greek gods to fill Mount Olympus…we are talking about institutions, pensions, and endowments funding opaque pools of leveraged loans that are not publicly traded, not stress-tested, and not fully understood[7]”.

As we write, there are concerns about the cracks in the private credit market – an issue which was brought to the fore by two recent private credit defaults. JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon suggested that “when you see one cockroach there are probably more. Everybody should be forewarned on this[8]” As one of the most respected bankers in the U.S., when Dimon speaks, we listen. The illiquidity of private credit could be problematic if there is a rush for the exits. Howard Marks had this to say in March 2025: “To paraphrase Warren Buffett, the tide has never gone out on private credit, meaning we haven’t had an opportunity to see its flaws. As far as I’m concerned, the main one is the possibility that some managers have been in such a hurry to scoop up capital and put it to work – so they could come back for more – that they relaxed their credit standards and failed to demand a sufficient margin of safety. If there’s ever another difficult period in the economy and the market, we’ll see the result.[9]”

We avoid alternative investments in favour of traditional and plain-vanilla common stocks, simple and high-grade fixed income securities and indices such as the S&P 500. In doing so, we protect your capital and keep fees low. In general, we believe, and our experience confirms, that complexity is your enemy in investing. Peter Lynch famously, and wisely, is quoted as saying, “Never invest in any idea you can’t illustrate with a crayon”. It is remarkable and perhaps surprising to you that many of the world’s greatest investors, like Lynch, avoid complexity and do simple things. Thirty years ago, we read the Richest Man in Babylon, originally published in 1926. That book spells out “The five Laws of Gold”, in addition to many other nuggets of investment wisdom. The 4th Law is stated as follows: “Gold slippeth away from the man who invests it in businesses or purposes with which he is not familiar.” The book has sold over two million copies and remains in print for good reason – it imparts timeless and valuable advice.

Our primary goal, our lodestar, is long-term compounding. We have firm conviction in our strategy because, based on our experience, it is the best and safest way to achieve this goal, taking into account yours and our attitude about risk. In short, we don’t know of a better way to both protect your capital and potentially earn above-average returns. Berkshire Hathaway has rarely incurred meaningful, permanent losses, all the while compounding at a rate close to 20%[10] since 1965. This result is testament to Warren Buffett’s skill but also, the merit if his strategy – an emphasis on simplicity, patience, quality and “value” (i.e. getting more in return than the price paid). Buffett, of course doesn’t try to predict the “macro” (the trajectory of the economy, markets, interest rates, etc.). In his words, “The cemetery for seers has a huge section set aside for macro forecasters. We have in fact made few macro forecasts at Berkshire and we have seldom seen others make them with sustained success.[11]”

We hope that you have enjoyed this letter. Of course, please call us anytime to discuss your investments or just to catch up. We are committed to providing you with a high level of service. To that end, we have added a new APEX team member, Jen Cunningham. Jen comes to APEX with a decade of experience in the mortgage business. Jen will be assisting you, our dear and valued clients, as well as APEX team members in administration and client service. Welcome Jen!

Best wishes to you and your family from your APEX team: Shawn, Mike, Denise N., Lisa, Marta, Jen, Denise E., John, Will, Jeannot, Andrene and Darlene.

Disclaimer:

This publication is for informational purposes only and has been prepared from public sources which are meant to be reliable. None of the information in this should be construed as investment advice. Speak to your Investment Advisor to learn if this product is right for you. Apex Investment Management is a tradename of Designed Securities Ltd. DSL is regulated by the Canadian Investment Regulatory Organization and a Member of the Canadian Investor Protection Fund Michael Begg and Shawn Malcolm are registered to advise in securities and/or mutual funds to clients residing in Ontario and B.C. The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of DSL.

[1] Butters, J. (2025). Are “Magnificent 7” companies still top contributors to earnings growth for the S&P 500 for Q3? https://insight.factset.com/are-magnificent-7-companies-still-top-contributors-to-earnings-growth-for-the-sp-500-for-q3?hs_amp=true

[2] Harring, A. (2025, October 6). Peter Lynch on why he isn’t in the AI trade: “I literally couldn’t pronounce Nvidia until about 8 months ago.” CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2025/10/06/peter-lynch-ai-trade-investing.html

[3] Carlson, B. (2025, September 30). Why is the Stock Market Up So Much in the 2020s? – A Wealth of Common Sense. A Wealth of Common Sense. https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2025/09/why-is-the-stock-market-up-so-much-in-the-2020s/

[4] Why fears of a trillion-dollar AI bubble are growing. (2025b, October 6). Financial Post. https://financialpost.com/investing/fears-of-trillion-dollar-ai-bubble-growing

[5] The calculus of value. (2025, August 14). Oaktree Capital. https://www.oaktreecapital.com/insights/memo/the-calculus-of-value

[6] Kelly, M. (2025, October 30). The Private Credit Bubble That Isn’t. Barron’s. https://www.barrons.com/articles/private-credit-bubble-worries-1acbcfc1

[7] Rivas, T. (2025, October 25). The stock market survives a bank scare. There’s too much riding on this bull. Barron’s. https://www.barrons.com/articles/stock-market-survives-bank-scare-73eb4419

[8] Revell, E. (2025, October 17). Jamie Dimon warns of “cockroaches” in US economy as credit concerns grow. Fox Business. https://www.foxbusiness.com/economy/jamie-dimon-warns-cockroaches-us-economy-credit-concerns-grow

[9] Gimme Credit. (2025, March 6). Oaktree Capital. https://www.oaktreecapital.com/insights/memo/gimme-credit

[10] CAGR

[11] Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (n.d.). Berkshire Hathaway Inc. https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2003ltr.pdf